Xenogears is available on the Playstation One and via PSN on Playstation 3, Vita, and Portable.

Xenogears was ahead of its time in a lot of ways.

Its plan for long-form storytelling across multiple games is something we see everywhere in franchises now. The blending of action-based and RPG-style combat feels like a precursor to the “action-RPG” niche that handily outnumbers turn-based games in the genre nowadays.

But more than anything else, its very existence reads like something of a head-scratcher.

Gearing Up

For starters, Xenogears took a two years of planning in addition to two more in development. Now, that doesn't sound like a whole lot at face value, especially considering how Square's recent flagship JRPG, Final Fantasy XV, was in development for a full decade under two different names, plus a full retail re-release's worth of iteration in the eighteen months afterward.

But games are more complex projects today than they were in the mid-'90s; As a nearer yardstick, consider that Final Fantasy IV through IV all came out in the span of three years, with little concurrent development; even nearer, standard practice for developer Square at the time was a hard two-years-and-no-more in development.

The bit about Xenogears that stands out, though, is the planning stage taking just as long. The idea started as a sequel to Chrono Trigger, of all things, before famously being rejected as a proposal for Final Fantasy VII. Too dark and complicated, apparently – and complicated would be an understatement.

Side note: getting pitched as a follow-up or alternative to an existing property is a classic blueprint for contemporary games.

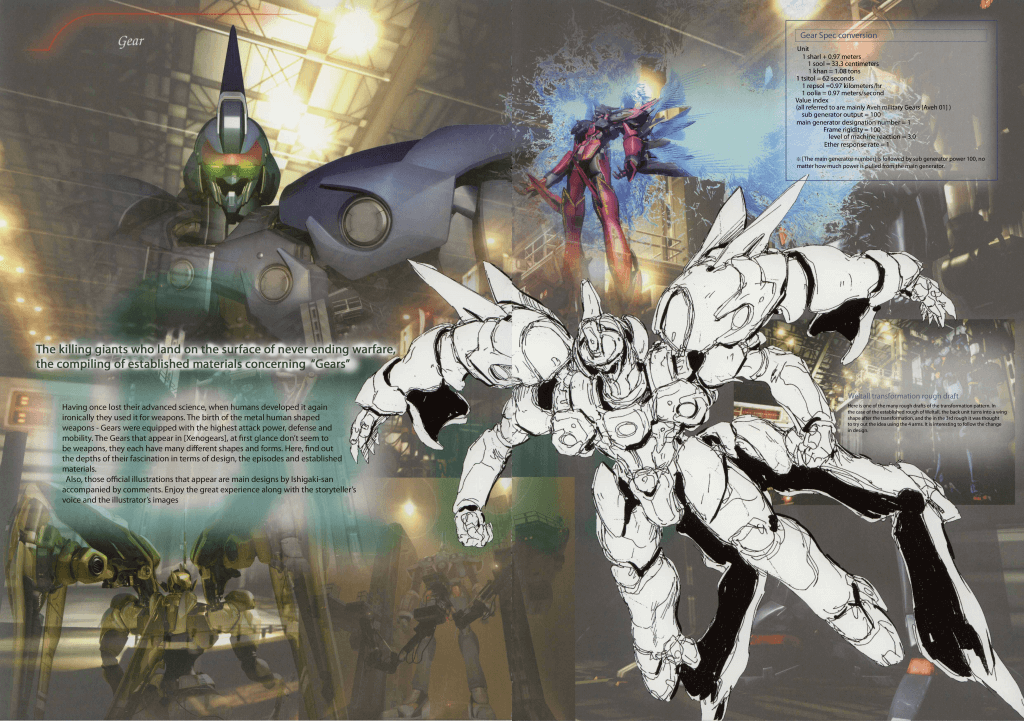

Even in early stages, Xenogears had sights set higher than a team of thirty could carry a game in 1996. Full-3D rendering (which didn't fully materialize). A focus on mecha designs (notoriously difficult to animate, especially in detailed cutscenes). A first-time director who had only previously worked in graphic design positions. And, most visibly in the final game, an absolute door-stopper of a story pitch.

That all isn't a bad thing, especially when you've got at least a little project security from working at such a JRPG juggernaut. But you might say the same about the original director of Mega Man making a well-funded Mega Man successor, and, well…

History sure proved that one out.

Never-Ending Dream

Xenogears‘ many many trappings between concept and release are hardly a secret. The original Playstation just couldn't keep up with the vision of a graphics-forward director. The relatively smaller team couldn't keep up, either, nearly running over time and budget. Its story was so big and heady that there were honest questions of whether it would even be worth attempting to localize.

Granted, all those things happened – if not quite as expected. The presentation was scaled back to a hybrid 2D/3D system, its localization effort was long and harried, and the story had to be limped over the finish line. Famously, he second half of that planned story is told primarily through text and snippets of cutscenes. That last one is arguably Xenogears‘ defining feature to this day: over-ambition leading to under-delivery.

All that without even getting into how Xenogears was originally just Part V in a six-part narrative. Cribbing Star Wars‘ leave-room-at-the-front numbering model aside, reasons why the others never happened feel a little self-evident.

Granted, director Tetsuya Takahashi did get to shop his ideas elsewhere – notably at Monolith Soft with a spiritual successor. Xenosaga carried many similar ideas and even one or two shared characters, plus returning staff down to the game's composer. Then a decade later Xenoblade similarly came about from of some of Xenosaga‘s ideas, making it something of a successor to a successor to a successor? And that one even lead to its own sequels and the meta-series' representation in the so-mainstream-your-mom-knows-it Super Smash Bros. Not bad in the long run.

But Xenogears itself?

It's a cult classic, sure, but always with the epithet “best half of a game I've ever played”. It makes for the truest example of a mixed-bag of a legacy.

Which makes it a dead ringer for a Kickstarter game, really.

You've got a director with ambition. They want to make a spiritual successor to a game everybody already likes, and the art they've pitched looks fantastic. But the project's team isn't that big, and things turn out to be complicated. Deadlines slip right by, and promises are toned down to match. Ultimately a release is just pushed out the door. The final product has its high points, but nobody is completely happy with the result.

And that's the lifecycle of Broken Age. Or Yooka-Laylee, or Unsung Story, or even Xenogears.

Do you remember when games were released in a complete state on day one?

Me neither.

Standing Tall

What is in the game has really captured the minds of Xenogears' fans, though. And that gives it a legacy to this day that's so much stronger than its glossed-over third act. Strong enough, in fact, that it has a crazy cult following for a sorta-one-off game with a mixed reception. Its various wiki pages tend to be disproportionately long, it's spawned some of the most ridiculously in-depth fan-sites I've ever seen, and Square themselves are still producing high-quality Xenogears merchandise twenty-one years on. Xenogears doesn't sound on paper like it should have a live concert tour two decades post-release, but that's the reality we live in.

There's some combination of its distinct character – not unlike the philosophical-slash-religious-mecha-opera that is Neon Genesis Evangelion – and its distinct incompleteness that draws people in. It feels like a rich setting with reams more to say than what ended up on screen.

And, by golly, that's exactly the case. The game's companion book, Perfect Works, functionally exists to relay 300 pages of mostly-cut extra lore. Fans translated it twice for lack of an official release, the demand was so strong. Oodles and oodles of promises of greatness, and a whole saga that has to just play out in our heads. But that may even be for the better. After all, the stories in our heads are way better than anything we can physically create.

So, in a sense, the idea of Xenogears has been way more valuable to me and others over time than playing the game ever could be. But the game effectively delivered that idea and provided a jumping-off point to learn about everything the creators intended to tell in the first place.

So… mission accomplished?

There's definitely the argument that the game is still bad. Objectively, yes, anything with such a gutted back half would be. But a bad game is far from the most damaging way to deliver something.

If your mechanic doesn't finish installing a tire right, someone gets into a car wreck, and you've learned the importance of safety checks. If you take a wrong turn at Albuquerque, you learn firsthand the beauty of the Cimmaron, but blow most of a day's travel. Whereas if you play Xenogears, you find a lot to dig into, but are out a tenner nowadays and a few dozen hours. Hours that are a delight to dig into, to boot. Really, the biggest thing people agree to be wrong with Xenogears boils down to that they wish there was more of it.

I guess the value in Xenogears depends on how you want to view stories and the things that tell them. As a product experienced moment-to-moment, it can leave a weird taste in your mouth. As a vehicle for ideas, it's fantastic in ways that extend past what's actually there on the disk.

In a way, Xenogears wasn't really delivered as a game in 1998. Just a part of it. The rest followed in a book, and in interviews, and in a splinter series, and in the many many fans who continue to dig into it even now. And none of that would exist if the project wasn't so ambitious to begin with.